Books

Worth a look

A Woman is No Man – Abuse and freedom in a Palestinian-American family

By Etaf Rum

(Harper Publishing, ISBN 9780062699763

Book profile by Margo Helman, MSW

The words on the back cover of this book were the first thing that caught my attention. I’m curious about any book that promises to give “voice to the silenced and agency to the oppressed”. I was standing outside by the “Mesila Park”, a narrow boardwalk and stripe of green grass that lines the old Jerusalem train track and runs through Jewish and Arab neighborhoods in the southern part of the city. Walking there on Shabbat or any afternoon, you meet a cross section of Jerusalem’s residents, sharing the space together. It’s hard to choose, but I’d have to say that my favorite point along the path is the free book kiosk that has become the Mecca of my reading life. One of several outdoor social libraries in the capital, where people can take, return and donate books, this one is friendliest to English readers, along with books in French, German and a sprinkling of Hebrew as well. It amazes me what books have fallen into my hands here. Books that I would never purchase and probably would never know of, have enriched my life beyond measure.

The words on the back cover of this book were the first thing that caught my attention. I’m curious about any book that promises to give “voice to the silenced and agency to the oppressed”. I was standing outside by the “Mesila Park”, a narrow boardwalk and stripe of green grass that lines the old Jerusalem train track and runs through Jewish and Arab neighborhoods in the southern part of the city. Walking there on Shabbat or any afternoon, you meet a cross section of Jerusalem’s residents, sharing the space together. It’s hard to choose, but I’d have to say that my favorite point along the path is the free book kiosk that has become the Mecca of my reading life. One of several outdoor social libraries in the capital, where people can take, return and donate books, this one is friendliest to English readers, along with books in French, German and a sprinkling of Hebrew as well. It amazes me what books have fallen into my hands here. Books that I would never purchase and probably would never know of, have enriched my life beyond measure.

This book, A Woman is No Man, by Etaf Rum, I had just pulled off of a shelf that nestled inside the refurbished bus shelter. When I flipped the hard cover open, I was further captivated by the first line, “I was born without a voice”. Then the rest of the first paragraph: “No one ever spoke of my condition. I did not know I was mute until years later, when I opened my mouth to ask for what I wanted, and realized no one could hear me. Where I came from, voicelessness is the condition of my gender.”

Later, on the same first page, was the clincher that had me take the book home: “You’ve never heard this story before. No matter how many books you’ve read, how many tales you know, believe me: no one has ever told you a story like this one. Where I come from, we keep these stories to ourselves. To tell them to the outside world is unheard of, dangerous, the ultimate shame.”

Later, on the same first page, was the clincher that had me take the book home: “You’ve never heard this story before. No matter how many books you’ve read, how many tales you know, believe me: no one has ever told you a story like this one. Where I come from, we keep these stories to ourselves. To tell them to the outside world is unheard of, dangerous, the ultimate shame.”

It’s true: I’ve never heard a story like this. I provide therapy for people coping with difficult relationships. I also teach people how to be calm during conflict. Still, a story like this has never been revealed to me. People who are experiencing such a comprehensive degree of loss of control and freedom don’t reach my office or the offices of my supervisees and colleagues.

Given that the novel’s characters left Palestine because of their difficult lives there, I wondered when I took the book home, if I would encounter antisemitism in its pages. There are a few compact sentences throughout the book that give information about the hardship of the families’ lives before immigration. Israeli checkpoints are mentioned. One character’s childhood history includes this sentence: “The truth was, Yacob’s family had been evacuated from their seaside home in Lydd when he was only ten years old, during Israel’s invasion of Palestine.” No more is said about this and there are no Jewish or Israeli characters in the book, not even for a moment. No individual soldier or Jewish neighbor is given a name, a face or even an action. Rum focuses only on the problems within her community. She includes the pain that the characters suffer before immigrating, as part of their story, but doesn’t let any feelings or political views she may have distract her from her mission: to tell the story of oppression of women in her community.

Two main story lines are revealed. The first is that of Isra. At age 17, Isra emigrates from Birzeit, north of Ramallah, to New York, with her new husband, whom she has met a handful of times. The second story is of her daughter Deya, born in Brooklyn. A quick Google search revealed to me a fact that isn’t spoken of in the book: Isra means night journey, specifically Muhammad’s journey in darkness, from Mecca to Jerusalem. Deya means light. The two women’s stories, encompassing much darkness and much grappling towards the light, are told in alternating chapters and the mother and daughter never interact directly.

There are other stories intertwined in the novel: that of Fareeda, the mother-in-law and grandmother, and that of Sarah, her absent daughter. Each suffers abuse at the hands of many other characters. Not only in their marriages do they suffer. They are educated for subjugation from girlhood. Their experiences are harsh. To give just one example, one young daughter is called a sharmouta, whore, and beaten when she spends the afternoon reading, which is forbidden to her.

We see the women deal with the violence and abuse in many different ways. One of the women collaborates fully with the oppression of her female relatives, playing a crucial role in keeping other women powerless. Others respond with resignation, physical escape or turbulent struggle from within the family.

Rum is remarkable in that she humanizes every single character, including the grandmother/mother-in-law who keeps the abuse in place, and even the abusers themselves. She also illuminates the choices of the women who stay.

No simple answers are given. The community is beloved while it is also merciless and cruel. There is a desire to stay connected to this strong family and culture, and a yearning to refuse to continue to suffer. In one of the stories told there seems to be hope that freedom will be reached. Other story lines end as terribly as one could imagine.

It’s not easy to tell our stories, but stories must be told in order to heal and to create change. In publicizing my work of teaching women and couples how to be calm and clear during conflict, I must virtually stand up in front of friends and family who know exactly the parts of my life that have inspired me to develop these tools and practices. Sometimes I share parts of my story. People whose lives are intertwined with my story, including my husband, know this and trust me to share in a mindful way.

What immense courage it must have taken to write this book. Courage to stand up to one’s family and community. Courage also to bare to the world these painful stories of terrible dysfunction and cruelty in her own community, which the author clearly loves. Rum spoke of her process in this interview. “…it took me a long time to overcome those fears and realize that in order for me to speak on behalf of women who are abused and oppressed, and to tell their stories — especially those women who are afraid to tell their own stories, because they’re ashamed, and because they feel like someone will come and retaliate, that I had to overcome that fear and tell this very authentic story.”

One of nine children, whose parents and grandparents were raised in refugee camps before some immigrated to New York, Rum wed in an arranged marriage at a young age. After a few years in the marriage and after pursuing an education, she realized she needed to break away in order to live as she wished. The Palestinian-American culture is, of course, a spectrum, as is our own. Rum points out that while her family was extremely conservative, with women being completely under men’s control, other families are more liberal. Rum found that though she became highly educated and worked in her field while still married, she was still beneath her husband’s rule. As a literature professor Rum “realized that stories of Arab-American women like me are not present in bookshelves, literature or libraries. I wanted to change that. Not only to represent these women who are suffering in a patriarchal society but also to give all women a voice.”

The title of the book comes from Rum’s experience growing up and being taught that as a woman, the right to self-determination did not apply to her. Seeking to do things that men in her community did, she was told she couldn’t. When she asked why, she was told that it was because she wasn’t a man. Rum explains that the phrase “A Woman is No Man” has a double meaning. On the one hand, a woman isn’t allowed freedom and self-agency simply because of her sex. On the other hand, a woman is uniquely powerful: she can see the toxicity of her community and work to keep it from defining the lives of her children. Rum says: “We can’t really just blame the men in our society. We have to look at the power that we have as women as well, to change the cycle”.

It seems that Rum has taken steps in her own life, in order to stop her personal “cycle of trauma and oppression”, at great cost.

Read this book to learn how abusive patterns in communities are held in place by everyone involved. Read it to understand the painful and complex decision of women who stay in abusive families and marriages, and the no-less painful decisions of the women who leave. Read it to experience a feeling of sisterhood with women struggling to define their own lives and stay connected to their own truth while coping with extreme mistreatment at the hands of the people closest to them.

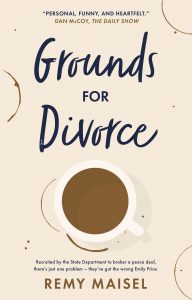

Grounds for Divorce

By Remy Maisel

(Book Guild Publishing, ISBN 9781913913380)

Review by Arnie Draiman

Remy Maisel cleverly opens with Senator Lindsey Graham’s actual remarks during a confirmation hearing for US ambassador to Israel, “I can’t think of a better choice to go to the Mideast than a bankruptcy lawyer, except maybe a divorce lawyer.” And with that, the tone is set for Maisel’s book, Grounds for Divorce.

Remy Maisel cleverly opens with Senator Lindsey Graham’s actual remarks during a confirmation hearing for US ambassador to Israel, “I can’t think of a better choice to go to the Mideast than a bankruptcy lawyer, except maybe a divorce lawyer.” And with that, the tone is set for Maisel’s book, Grounds for Divorce.

In a case of badly mistaken identity, Emily, a down-on-her-luck intern, is recruited by the State Department to solve the Palestinian problem. Only this time they want it handled as a divorce settlement.

It is an easy, enjoyable read, though Maisel’s writings mirror Woody Allen’s writings, only they are more neurotic. She takes us on an emotional roller coaster, filled with intrigue, and gives us a hidden gem – the complete backstory – sandwiched in-between the bookends of her main tale. Her writing is a bit disjointed at times, with scene changes often taking place quite abruptly, like a typical turbulent overseas flight.

We meet Emily Price, our protagonist, and her entire array of conventionally unconventional characters. We can’t help but like Emily, even if she prefers Bissli to Bamba, is addicted to beta-blockers, and uses a BlackBerry. She despises bodyguards and bigamy, but embraces bargaining, bird-nesting, and breakthroughs.

Emily Price feels strongly that one should “divorce the emotional and religious elements from the main points of conflict in order to pursue a mutually agreeable result.” Is our Emily up to the task of solving the crisis in the Middle East, when she is having sufficient difficulty solving her own family crisis, not to mention her own personal predicament as well?

Maisel brings the story to a close in rapid-fire fashion with a healthy dash of reality tossed in, and our understanding of Middle East politics probably none the worse for wear.

Suitable for mature teens and older; contains occasional profanity.