A Fiery Message

Written by Yaffi Lvova, RDN

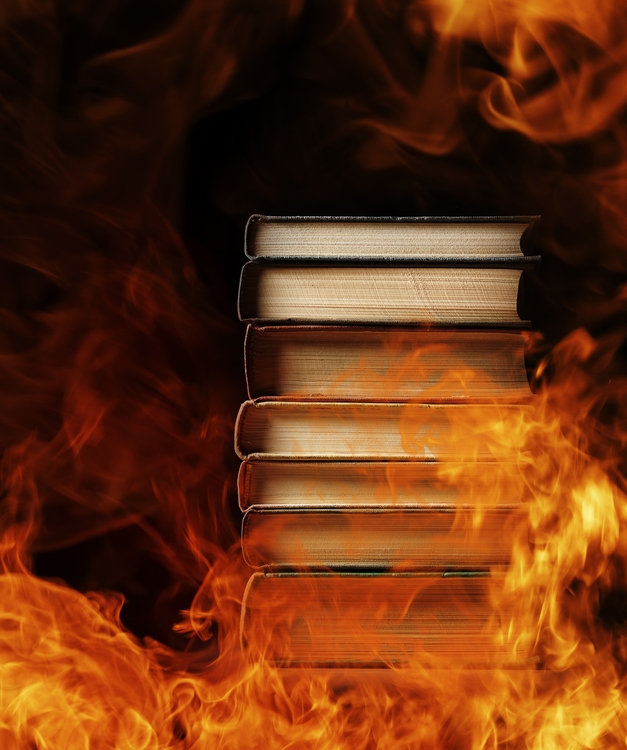

The air is thick with smoke. Pages curl back on themselves, succumbing to the heat. The letters roll and curl into the flames as if mocking their initial descent onto the page. But there is something else in the air. Anger? Retribution? Rage? And is the result a wave of confidence, of optimism, of relief on the part of those offended by the words contained within those pages? Have the bonfires met their objective?

Smell the smoke in the air and look around. Where do you think you are? Possibly Paris in 1242? Germany in 1933? Or perhaps it’s Venice in the early 1700s. Are you a child holding your mother’s hand as you smell the burning manuscripts of Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, the Ramchal, accused of being a false messiah fast on the heels of Shabbati Tzvi?

When searching “book burning history,” a Smithsonian article pops up. A Brief History of Book Burning, From the Printing Press to Internet Archives. It’s not surprising that the first image in the article is of Hitler Youth at a book-torching event in 1938. That’s a common point of reference for this subject matter. But that’s not where you are.

The earliest record of intentional destruction of literature was in 213 BCE when the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang held a bonfire of books in an attempt to bring all information under the control of the government. Book burning often arrives as a sizzling side dish to delicious conquest. The famous library in Alexandria was burned numerous times, including in 48 CE when Caesar chased Pompey to Egypt and again in 640 CE when Caliph Omar invaded Alexandria. All of that knowledge has now ceased to exist. Histories lost, medical advances and mathematical philosophies gone. Proof of civilizations up in smoke.

It begs the question: What might we have gained as a society from those pages?

As discussed in the Talmud in Masechet Megillah, books are sacred and holy. They should be treated with respect. Houses should be full of them and they should be open on the table during Shabbat and on all other days as well. If a holy book is damaged it must be treated in a certain and sacred way. Jews are the most ancient bibliophiles.

Sometimes, however, it’s discovered that the source of a book was impure. And then it becomes profane. A book destined for the flames, as it may be.

On January 25th, 2022, a bonfire was lit on a grave in Petah Tikvah. It contained the contents of a private library in Bnei Brak, a library that had sent these books to be torched, seemingly in contrast to the established Jewish views. These books had been written by someone who no longer held the respect of the community–someone who taught parents and educators how to give their children a voice, all while suppressing those voices for his own proclivities.

Chaim Walder’s books lined the shelves of families around the world. Kids Speak 1-12 sold over two million copies, advising kids on sensitive topics and advocating for emotional expression. The current Amazon listing describes Kids Speak: “In Kids Speak, kids open up, tell their own stories, express their feelings, and share unusual experiences as well as their reactions to them.”

Walder received the Israeli Prime Minister’s “‘Magen Hayeled” (“Child Protector”) award for his work in 2003. Ariel Sharon said he displayed “sincere concern, dedication, and belief in the ability to improve the situation of children in the community.”

In early 2021, reporting by Haaretz journalists brought to light another controversy involving sexual abuse by another influential and respected public figure. The fallout of that event included a flood of tips regarding instances of child abuse. The name that came up the most often was Chaim Walder’s. These new claims

served to validate the initial claim against Walder, 25 years ago, as well as another case filed and dismissed over a decade ago for lack of evidence.

Twenty-five women ended up coming forward, one for each year of Walder’s public work. A rabbinical court was assembled, led by the chief rabbi in Tzfat. For twenty-five years, Walder worked as a therapist, writer, and educator, and was the person who founded and managed the Child and Family Center in Bnei Brak. He was now to be put on trial amidst allegations of abusing girls and women in his therapeutic care.

On the same day that an investigation was opened by the police, Chaim Walder was found dead on his son’s grave, from a self-inflicted wound. With him was a letter proclaiming his innocence.

Many Jews prefer to listen to Jewish music because it’s believed that the intention behind the work of creation is as important as the final creation itself. Music from an unholy source, however beautiful, would be considered unholy. The unwitting consumer could accidentally ingest the unholy message and suffer spiritual repercussions. The same is being applied here.

Ayelet Katz, MA, MLIS, says that confusion regarding the status of Walder’s books is complex and many people have mixed emotions about their content. “Judaism doesn’t see holy books as a binary of either holy or profane–there are gradations of holiness and any book with religious value could arguably be considered to have some degree of holiness and treated commensurately. Including Walder’s books pre-revelation. Once he was exposed, perhaps that changes. Or perhaps it’s far more complex. Can content be separated from author?”

Taking a flame to a book–it doesn’t strike the viewer quite the same as the theoretical image of a garbage truck dumping books into a lake. The sight of a flaming page immediately grabs the viewer and pulls them in. A shape inhale. What happened?!?

Public displays of the destruction of Walder’s books on social media intended to make a powerful statement to the victims–victims who continue to see news stories defending Walder. One woman reportedly killed herself after seeing the way her community celebrated his life. Bracha Halberstadt, a trauma psychotherapist in Lakewood, NJ, says that the number one issue that has shattered her clients is the disbelief, the victim-shaming, and the requests that are made to avoid speaking ill of the dead. The stance that we should speak only positively of Walder is one that threatens to dismiss the validity of a victim’s experiences.

It’s not easy for a Jew to burn a book. As Jewish people, we have an uncomfortable history with the very concept of book burning. The German playwright Heinrich Heine famously said, “Wherever they burn books, in the end, will also burn human beings.” Refer back to the first image in the Smithsonian article. Although the quote was from his 1821 play Almansor and referred to the burning of the Quran during the Spanish Inquisition, it was quite prophetic. His

own books ended up among those burned on Berlin’s Opernplatz (Opera Square) in 1933.

Is book burning inflicting further harm? The thousands of children who grew up with these books are grown adults, seeing their own children tote their own copies home from school. These adults recall lines from Walder’s books, seeing them through new lenses and feeling the reality of the situation creep into the space that had been their own comfort.

Therapists were busy fielding calls from relapsing clients while combing through their own tangled thoughts. Perhaps Walder had even inspired them toward a career in therapy.

Is it ever ok for Jews to burn books? According to Ayelet Katz there are three possible answers to this:

- Book burning is never ok.

- Book burning might be acceptable on a case-by-case basis, particularly when there is a therapeutic benefit.

- Book burning isn’t an issue unless it’s a holy book.

She goes on to say, “The issue for me is that the problem with Walder’s books is that it doesn’t fall neatly into any of these categories.”

One of Walder’s victims writes in a public letter on the topic:

“Not once in all my years of education did a Morah, Menhales, Mechaneches, or anyone else in school inform me that Rabbis can be bad and do very bad things to little girls. We received no warnings of what to do if a man touches you…”

Warn. Educate. Use this passion to create community resources that provide a safe space for reporting and for healing. That may or may not come alongside a platter of Kids Speak a Flambé. There has been good that has come of all of this. Communities are putting much more effort toward prevention programs, demanding increased openness from authority, and more safeguards are being put in place in therapy to protect the vulnerable.

Avigail Gordon, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist in New York, says,

“For some people, the book burning is a healing act, and for some people, it’s a traumatic trigger. It defies easy categorization. Which maybe is the point, after all – that we need to be able to hold these competing truths and competing needs. Chaim Walder’s books helped people. They also allowed him to hurt people in inexcusable ways. That’s what makes this hard. We need to hold space for both the people who need to burn them and those who can’t bear to see books burned.”

ZA’AKAH, an organization fighting Child Sexual Abuse in Orthodox communities, has opened a hotline on Whatsapp for anyone struggling with these events.

They can be reached at 888-492-2524.

It’s not easy for a Jew to burn a book. As Jewish people, we have an uncomfortable history with the very concept of book burning.

Related Articles

Related

Is it OK to Pray at a Grave?

“I am going to the grave of Rabbi Meir the miracle worker, to pray that I find my lost wedding ring.” “I am going to the Amuka, the grave of Yonatan Ben Uzi’el, to pray for a shidduch (marriage partner).” “I am going to visit the grave of Rabbi Gedalya Moshe of...

You Can Eat It, But Is It Actually Food?

We thought we were eating food when we really weren’t. According to Google, food is defined as “any nutritious substance that people or animals eat or drink, or plants absorb in order to maintain life and growth.” Typical American snack food like potato chips, soda,...

Making Our Celebrations Less Stressful and More Meaningful

Celebrations (smachot) highlight happy occasions and milestones such as Bar and Bat Mitzvahs and weddings. They are special times we look forward to with great anticipation for many years. Over the last few decades, however, both making a simcha (celebratory occasion)...