Why Won’t My Child Just Eat? Feeding the Neurodivergent Child

Written by Yaffi Lvova, RDN

It’s the most natural thing–a baby is born and crawls to the breast to nurse. Eating. It’s one of our basic biological functions.

So why is it so difficult?

When friends and family give recommendations that fall flat, and when the advice from the best experts still doesn’t work, when you’re left with a battlefield at each and every meal, you may feel like screaming, “Why won’t my child just eat!?!”

Feeding the neurodivergent child is a challenge. It’s also a challenge to provide good advice for the general neurodiverse population. Each child is a unique flower with their own petals (and thorns). Often, feeding advice must be tailored to the family and to the individual–and that’s where the advice found on social media may lead the concerned parent astray.

So what’s the answer? First, put yourself in their shoes. Think about the atmosphere during dinner prep:

The noise of the pots and pans, maybe water running or dripping…

The heat of the oven or stovetop…

The smell of the veggies roasting…

The hectic sight of mommy getting things ready for dinner…

Is that all? Maybe someone is asking for help with homework and someone else is dumping LEGOs on the ground. The simultaneous stimulation of multiple senses at once are not just distracting, they are dysregulating, leaving a child with decreased ability to manage their emotions. Dinner hasn’t even started yet. Once the meal is on the table, the fifth sense is stimulated as well. Taste.

For sensory and autistic children (and adults), each sensory experience is amplified many times over what that same experience represents to someone neurotypical. What might be a slight annoyance for the neurotypical person, the autistic child might experience as an all-consuming ordeal. If each sense is amplified, consider what that might feel like at mealtime. Every sense is activated. Every sense is amplified. Each shouts for undivided attention, with the result being a child who is completely overwhelmed.

The fight or flight biological response is triggered, meaning that the hunger signal turns off, digestion slows, and the body focuses on mere survival.

It’s easy to see why many kids seek comfort at the table with familiar foods, some rigidly so. Many parents see food rigidity, fidgeting, and shortened meals as behavioral concerns. They believe that the child is trying to manipulate them. If instead, they can see it from the child’s perspective, it becomes clear that these behaviors are simply communication.

I am dysregulated. I am overwhelmed. I need your help.

The parent’s options in each case will depend upon many factors, but the goal will be to help the child find comfort and safety, adjusting their own expectations in favor of the child’s needs.

How to get this child to eat

“It’s not your job to get your child to eat.” Ellyn Satter is a dietitian and therapist who introduced and developed the Division of Responsibility. In this feeding model, the parent is in charge of:

- What is served

- Where it is served

- When it is served

The child is responsible for determining:

- Whether they will eat

- How much they will eat

The purpose of the method is to be responsive to the child’s needs while providing appropriate boundaries and not overstepping their own autonomy. Overstepping these lines can result in a breach of trust: If I come to the table, they will force me to eat. The table isn’t a safe place.

Many parents immediately respond to this concept by asking the obvious, “What about nutrition?” That will be discussed further on. Nutrition is a concern. The parent-child relationship and the child’s self-image are taken into account and prioritized above physical nutrition consumed in any given meal or day.

Why doesn’t the standard advice work for me?

If you are the parent or caretaker of a neurodivergent child or family, you may have tried the standard advice unsuccessfully. There are a few reasons for that:

1. Sensory processing differences. The standard guidelines for feeding your child assume that your child (and you) are neurotypical. Looking closely at Ellyn Satter’s advice past the main guidelines of Division of Responsibility, it’s advised that by following her framework, the child will be healthy, behave well at the table, and be an appropriate weight. Expectations and definitions are often different in the context of neurodiversity: “good behavior” must be reimagined with the strengths and possibilities of the specific child in mind.

2. Other sensory processing differences. Aside from sight, smell, sound, touch, and taste, we also have three more integratory senses–this is how our body communicates with itself. We also have the vestibular system (sense of head movement), the interoceptive system (sensations from muscles and joints), and the proprioceptive system (hunger, fullness, other biological stimuli). Some neurodivergent children are lacking, or less sensitive to the interoceptive system, meaning they can’t necessarily identify the feeling of hunger or fullness. They may keep eating, even to the point of being sick, just because they can’t feel when to stop. An occupational therapist can help build and restore that connection.

3. More sensory processing. Food neophobia is a normal stage kids enter around the time they begin to walk. This is a general nervousness around unfamiliar foods which can be overcome with food exposure. However, for the neurodivergent child, this isn’t simple anxiety. It’s not just a dislike or fear of a food. It’s as though someone has put a raw chicken breast on the plate for dinner. Orange slices can feel like cactus in the mouth. No amount of exposures will overcome these sensory experiences, so they must be worked around.

What might be a slight annoyance for the neurotypical person, the autistic child might experience as an all-consuming ordeal.

Do kids really need variety?

Pursuing a plant-forward diet is wonderful. Variety is the spice of life! Nutrition professionals, including this author, continue to extol the virtues of eating the rainbow. That is a beautiful thought and it does come with benefits, but when that goal comes with so many huge hurdles, some putting the child’s emotional health and mental health at risk, a closer look is warranted.

We don’t actually need variety in the diet in order to meet our needs. In fact, if you were to use a nutrition analysis program to analyze a given child’s diet over the course of a few days, you would likely find that they actually are pretty good at meeting their nutritional needs. When a child isn’t meeting their nutrition needs, there are fallback methods like multivitamins and other types of supplementation. A registered dietitian can help determine the child’s nutritional status and needs, as well as ways to meet those needs comfortably.

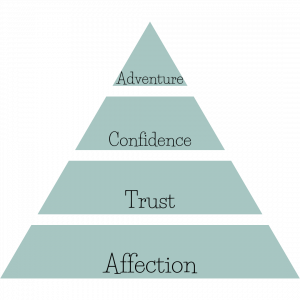

Climbing to the top of the pyramid

Affection is built on trust. Once affection is attained, confidence can be gained. A sense of adventure only comes after all of that. This is a simplified version of Maslow’s explanation of human needs. When we have our basic needs met, only then can we progress toward the more lighthearted aspects of life.

Affection is built on trust. Once affection is attained, confidence can be gained. A sense of adventure only comes after all of that. This is a simplified version of Maslow’s explanation of human needs. When we have our basic needs met, only then can we progress toward the more lighthearted aspects of life.

The very top of this image is “Adventure.” That’s where the child feels safe enough and confident enough to explore a new food.

First, examine whether getting to the top is an appropriate goal for the child. For some, having a goal of adventure and variety is completely appropriate. For others, it will cause undue stress, increasing the tension at the table and further damaging the feeding relationship.

By stepping back and creating small, age- and developmentally-appropriate goals for the specific child and family, all expectations can remain appropriate and subtle successes can be celebrated.

With the neurodivergent child, senses are often overwhelming. By experiencing each of the five senses on its own, a person can become more familiar, and therefore less anxious. Laughter mitigates anxiety. It also helps to create new associations–new neural pathways–which can help the child feel less cautious around food.

Food play is a great way to provide a non-threatening food experience. By bowling with Brussels sprouts or smashing overripe melons, the child is free to experience the food in a situation where no eating is expected. Other ideas for gentle food exposure include picking your own fruits and veggies, doing art with a food medium–like painting with orange slices, or just drawing a tree that has oranges on it.

Coming full circle

There is a lot of pressure on parents to be perfect. Often, adults don’t trust their own bodies because of unfortunate nutrition messaging they may have internalized. This isn’t a setup for success on the part of the parent nor the child.

Shift focus to preserve the relationship between parent and child. Value the child’s comfort and confidence in the eating process. If there is a concern, or if you simply want to feel more confident in your approaches, seek out a feeding therapist appropriate to your child and to your feeding obstacle.

Related Articles

Related

Is it OK to Pray at a Grave?

“I am going to the grave of Rabbi Meir the miracle worker, to pray that I find my lost wedding ring.” “I am going to the Amuka, the grave of Yonatan Ben Uzi’el, to pray for a shidduch (marriage partner).” “I am going to visit the grave of Rabbi Gedalya Moshe of...

You Can Eat It, But Is It Actually Food?

We thought we were eating food when we really weren’t. According to Google, food is defined as “any nutritious substance that people or animals eat or drink, or plants absorb in order to maintain life and growth.” Typical American snack food like potato chips, soda,...

Kids & Technology

The scene is familiar. You try speaking to your kid and hear a grunt in response, you turn around and you see that they are totally engrossed in their device. You call them again, again you hear a grunt. Finally you get super close to them and say, “It’s time to...